EDURAN NAVIGATOR

Quarterly Market Review with an Outlook.

Zurich, 3th October 2020

“Price & Value”. Dramatic economic slump and the stock is back or close to record levels again. What appears to be contradictory at first sight is a rational adjustment to again lower interest rates and hence an increased lack of alternatives which continues to make equities the asset class of choice.

Market Review

Following the market correction in March stock markets and risk assets in general have rebounded and consolidated for most part of the third quarter. The virus has changed many things and some even say a new era has begun. In regards to the stock market other than the correction in March one could argue we are still in the same, or at least very similar environment as before: a lack of alternatives which forces money going into risk assets such as equities, even more than before. With the slowdown in the economy some earnings will suffer and hence one outcome would be one has to pay more for fraction of the return.

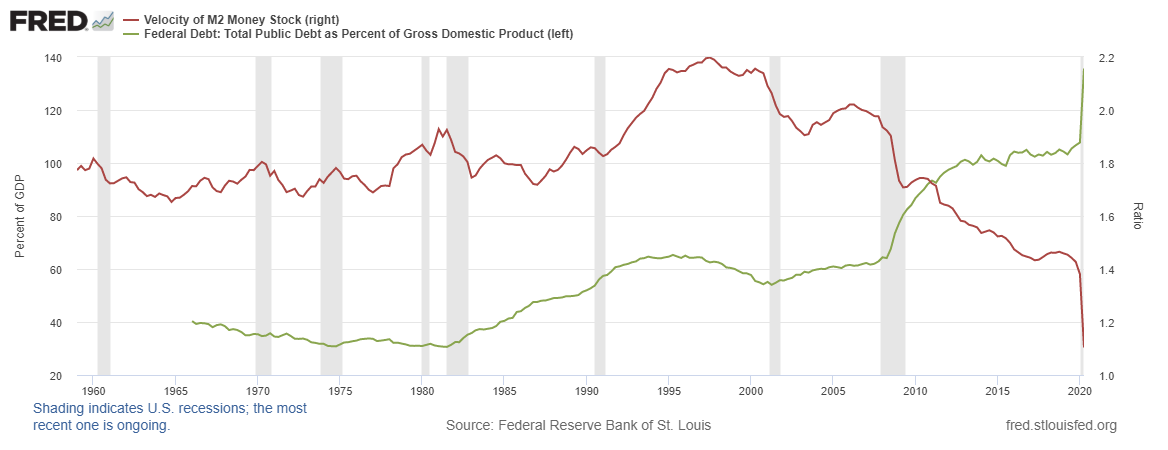

Many things of what the virus has brought to light has already been in place beforehand. For example the geopolitical tensions including the dispute between communist China and the USA and the “free world”. China, which has well understood to attract capital and also accessing western technology (copying it) over the past few decades, is advancing and challenging the USA as a hegemon. the western economies seem to suffer more than the Chinese at first hand. Globally though the debt situation has become more dramatic which is likely to slow down future growth once again (ceteris paribus). Since the 80s, debts have been rising steadily worldwide, even in the ostensibly rich West and with the virus, as the graph below is illustrating, debts have risen to record levels in many places.

While credit growth initially supported growth, it has now become indispensable. Without credit growth, many economies would be endangered to suffer a recession. Now with the virus economies have slipped into recession, at least in the short term, due to measures taken such as lock downs etc. But even here, there were many indications that economies were slowing down and at the brink of a recession before the virus hit.

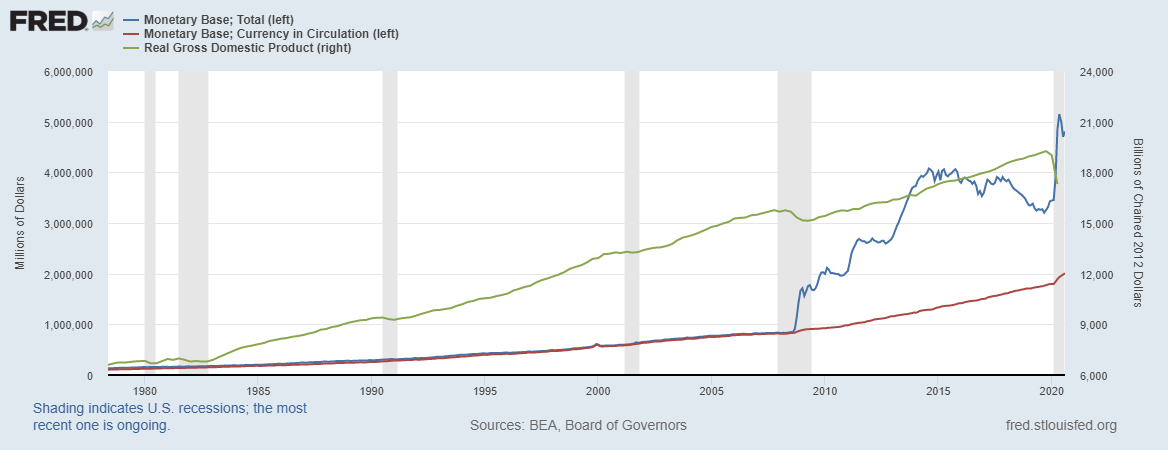

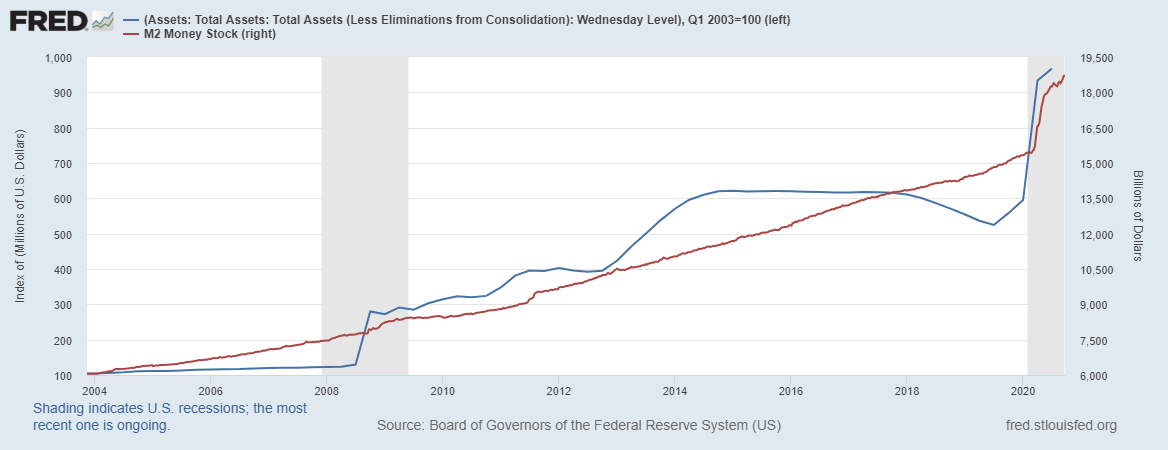

An other important topic, the monetary policy, which has been a recurring topic in our quarterly letter (as a tool to intercept or mitigate crises), is on the plate once again. Initially, the central banks used interest rate cuts to support crisis markets (LTCM, tech bubble burst). Over the course of time central banks have implemented more aggressive forms of open market interventions where they buy securities directly in the market (QE). Primarily it was for government bonds and lately they even have started to to buy, at least indirectly via corporate bond ETFs (or even shares, as in the case of the SNB), other securities on top of it. The balance sheets of the central banks have been inflated to unprecedented levels.

If a central bank buys securities, the selling commercial banks do not receive “real” money in return, but are credited an increase of reserves which they hold at the central bank. In order for this to become “real” money, the commercial banks have to grant loans. The commercial banks have granted loans, but as the figures regularly show: too few for most part of the time (assets grow but M2 is lagging).

A new development caused by the “corona crisis” is that politicians (governments) are now granting loans. This means that “real” money is fed directly into the economy. In contrast to central banks, which cannot directly fuel inflation without commercial banks or without the active involvement of the economy, the continuation or expansion of “corona cheques” could breathe new life into inflation.

As shown in Figures 1, 2 & 3, the money supply (M2) has indeed increased, but the velocity of circulation has decreased noticeably. For decades the velocity of money has been in range which has been left to downside with the start of QE in 2011. If we compare the velocity of circulation with the ratio of total debt to gross national product, this also shows that if debts make up around 2/3 or more of the gross national product, the velocity of circulation weakens. With the virus from China, it has almost come to a standstill.

In short, as a global economy we seem to be deeper in the swamp than before. The credit situation is dominating the scene and while central banks are doing everything in their power, the weak demand side for loans and investments seems to be a significant part of the problem. Growth and hence demand for credit is needed to help the situation.

The reality points toward the opposite which is overcapacity on the supply side and a deflationary pressure.

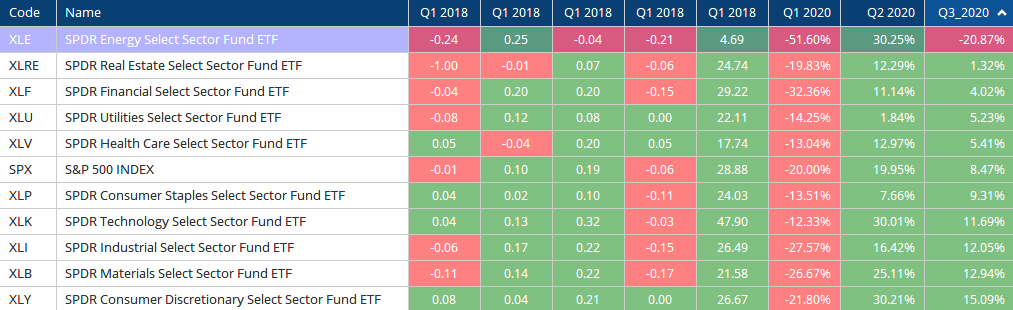

Stock Market

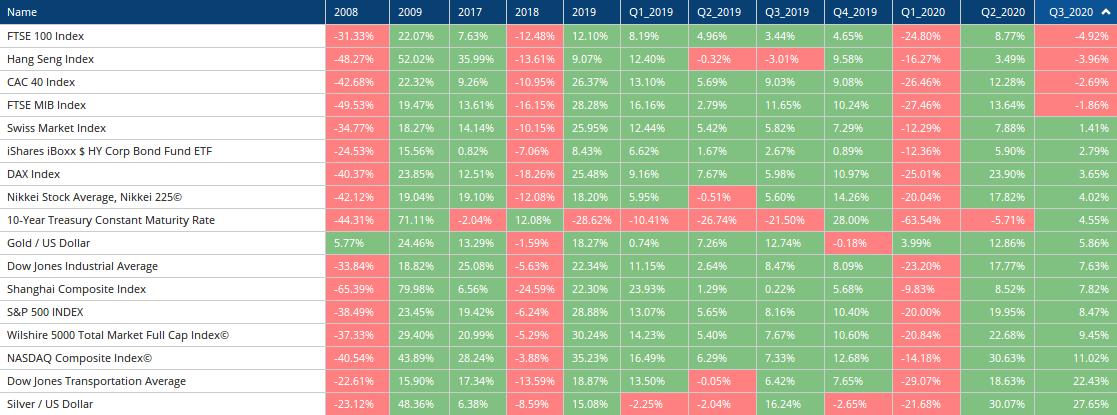

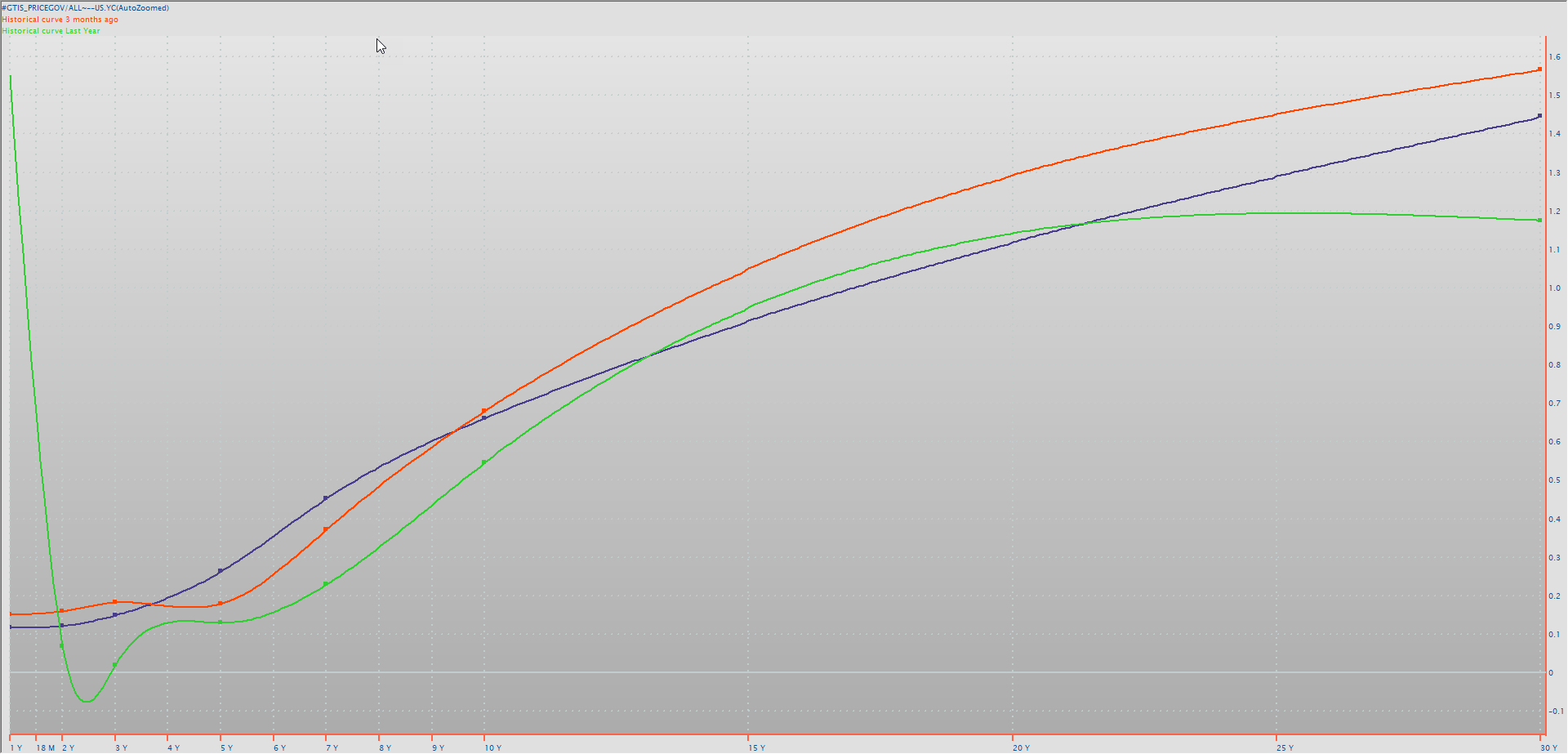

The stock exchanges consolidated over the 3rd quarter, or continued to recover, albeit at slower pace than before. The government bonds yields, specifically on US government bonds, were also at a similar level at quarter-end as at the beginning of the quarter.

The main drivers of the recovery on the stock markets was again momentum which typically goes with growth stocks. However, towards the end of the quarter, profit taking began to kick in and made the technology sector give in a bit. Sectors such as industrial production were able to hold their own for most of it.

Above all, consumers do not seem to have been put upon by the crisis, maybe because they were able to save money during the lockdown. The sector is back at pre-crisis levels and close to its all-time high.

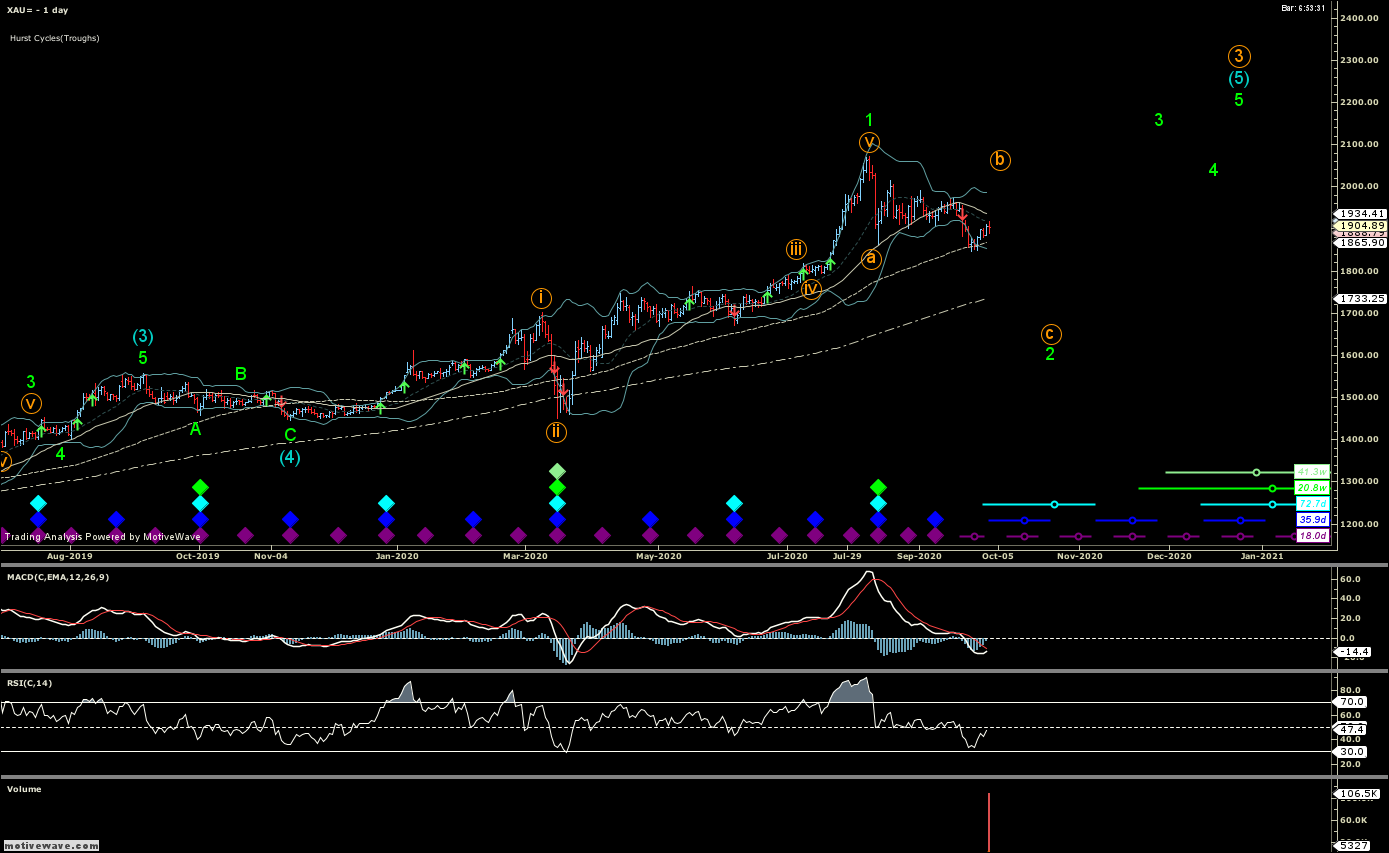

Gold and silver have erupted upwards and – in the case of gold – reached new record prices. Silver reached prices of almost USD 30, last seen in 2013. But here, too, both began to consolidate towards the end of the quarter.

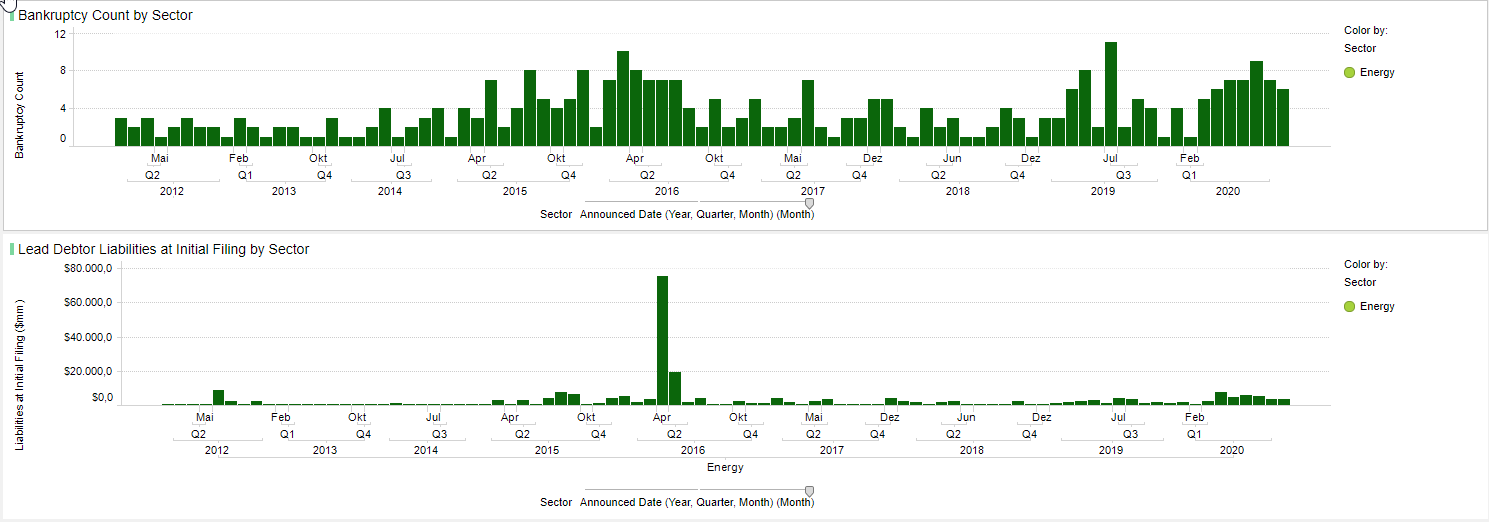

The energy sector is still suffering from the of the collapse in oil price earlier on. The economy is suffering from the virus, and so is the oil price. Oil prices below USD 40 an ounce make things difficult for many companies and hence does not help refinancing debts. There are indications of an accumulation of bankruptcies of companies in this sector.

Interest Rates & Capital Markets

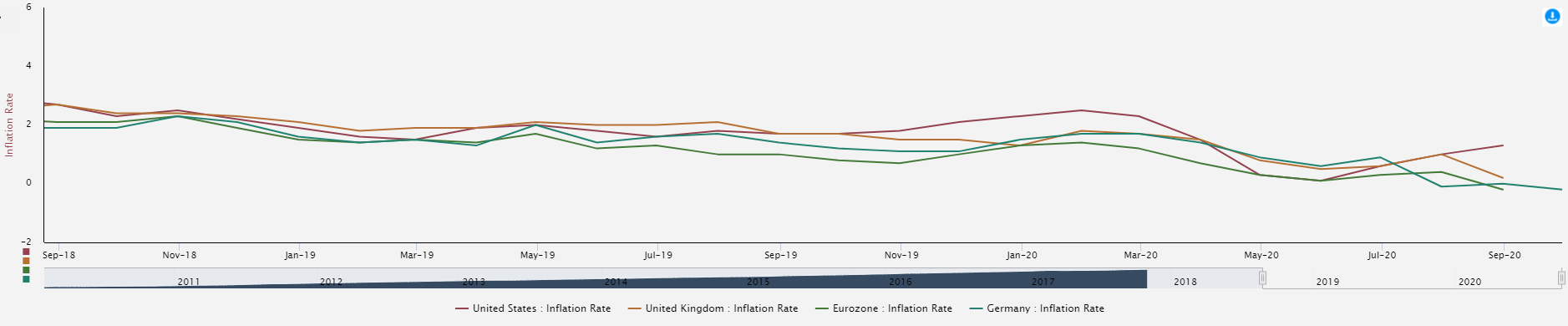

On interest rates some calm set in; the volatility decreased noticeably. In contrast, inflation expectations in the markets have been breathed back to life. Downward pressure on interest rates is likely to persist even if bond sales have recently prevailed, resulting in a technical downward breakout and consequently higher yields. It remains to be seen whether it is the beginning of a new trend – loe probability. There are many indications that interest rates will come under pressure again and that the weakness in bond prices is a temporary one.

Even if the inflation rates have largely, and especially for the developed economic areas, tended to decline, there are fears on the market that inflation may flare up. Not least because of the recent and massive expansion of the central bank balance sheets. With the additional money that has entered the markets via governments, and may be added again, at least a temporary, minor flare-up of inflation would be possible.

On the other hand, there are some signals that deflationary tendencies will continue to have an impact. It is a vicious circle. With interest rates low, it is difficult to keep credit expansion going – which is needed to keep the money supply from shrinking. Due to the low interest rates borrowers could increasingly use their liquidity to repay their debts instead of interest payments. The low interest rates are also evidence of diminished demand for credit. From this point of view, it is important to keep an eye on the banks’ credit activity. If more and more loans are taken out, this can be seen as a “resurrection” of the economy, and inflation could rise. Which would herald the U-turn in interest rates.

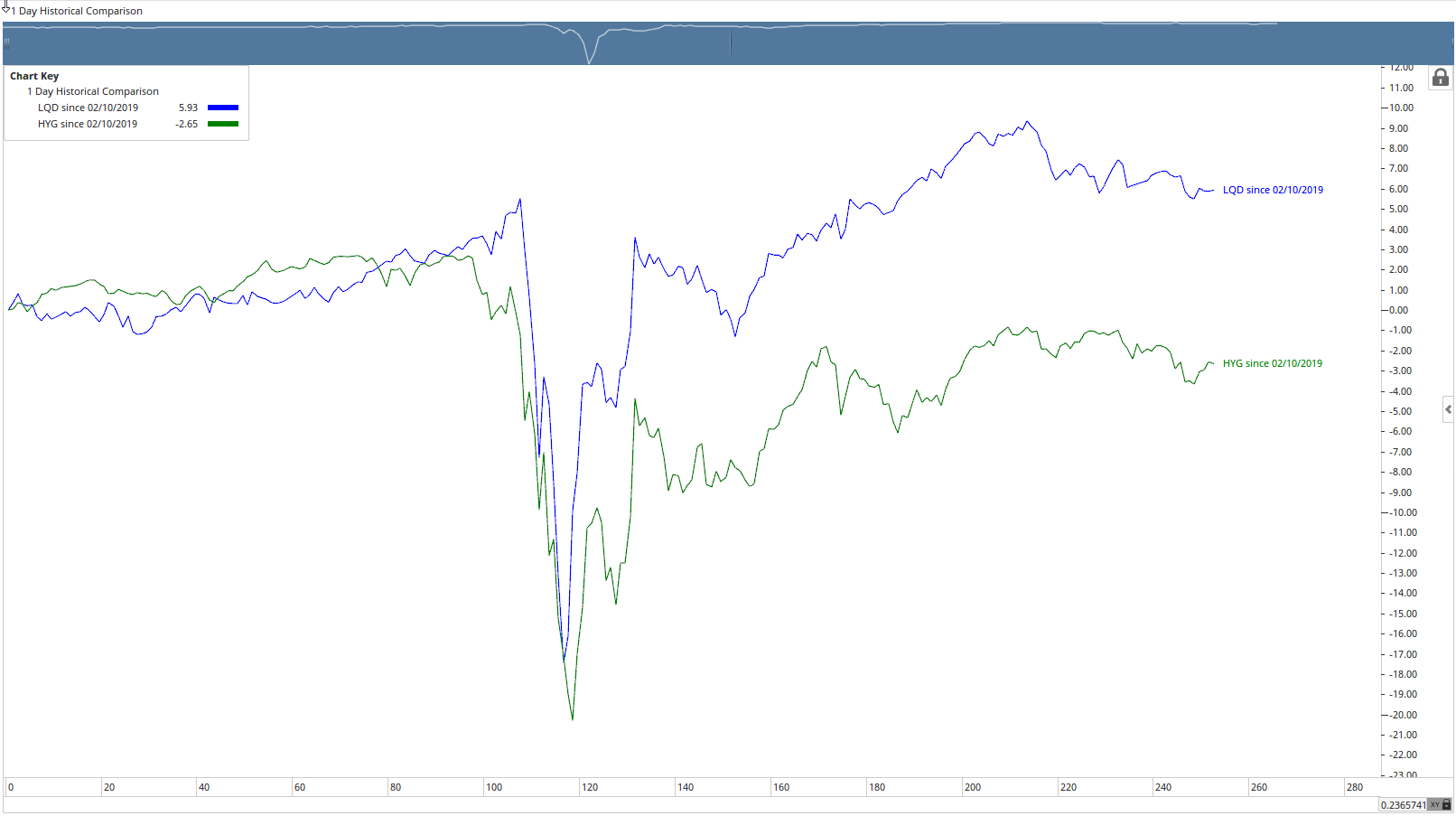

The risk premiums diverged in the phase after the virus shock, and remained mostly unchanged in the third quarter (shown above by the price trend of the ETF for high-yield bonds with correspondingly weaker balance sheets versus the ETF for high-quality bond debtors). To a certain extent, this separates the wheat from the chaff; quality has recovered, while in times of declining economic activity, companies with weak solvency are lagging behind.

The yield curve has become somewhat steeper at – as described above – a generally lower level. With the easing in the second quarter, the curve flattened in a shy way compared to the stock market’s low of 19 March.

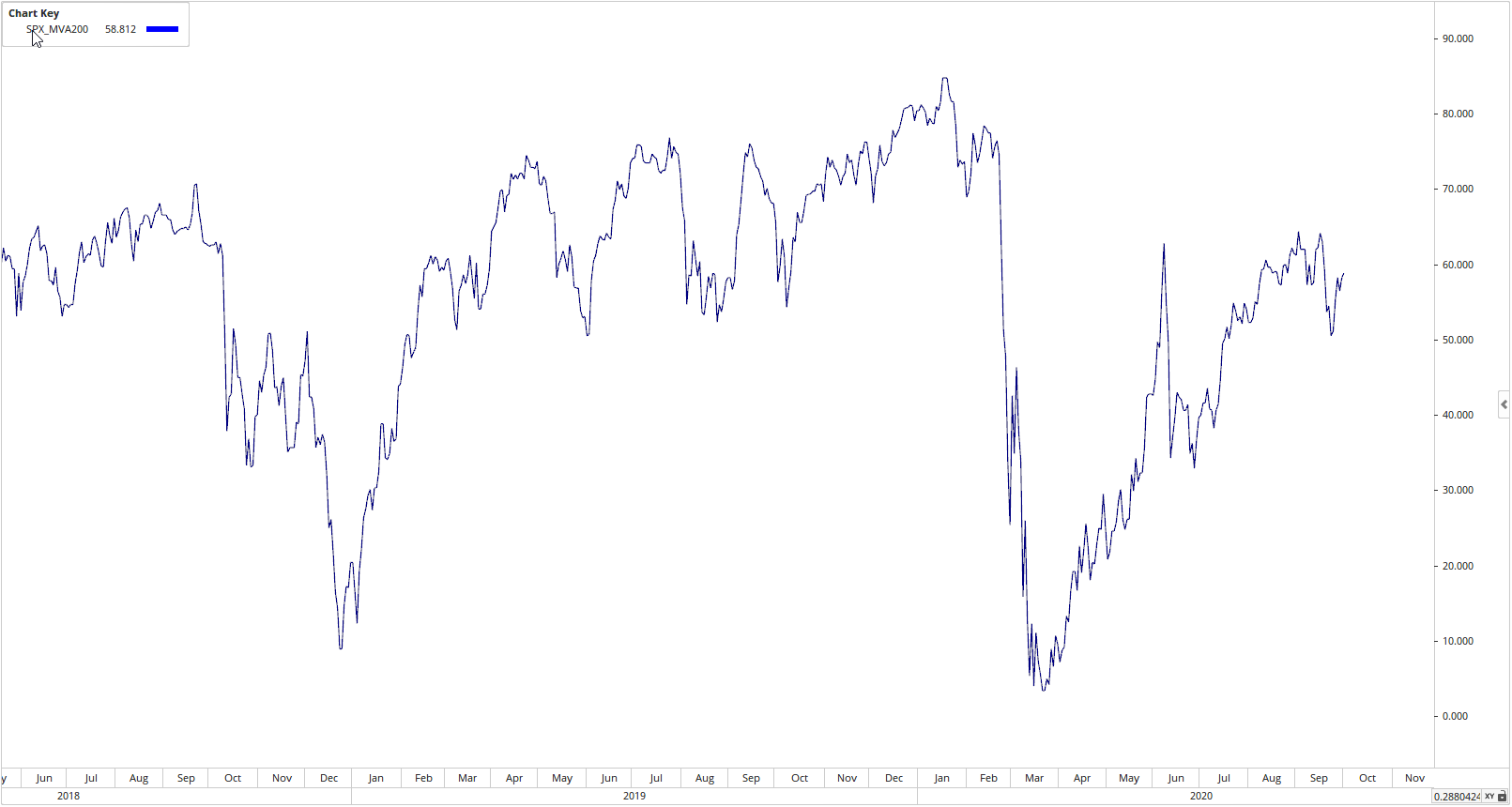

Market Technicals

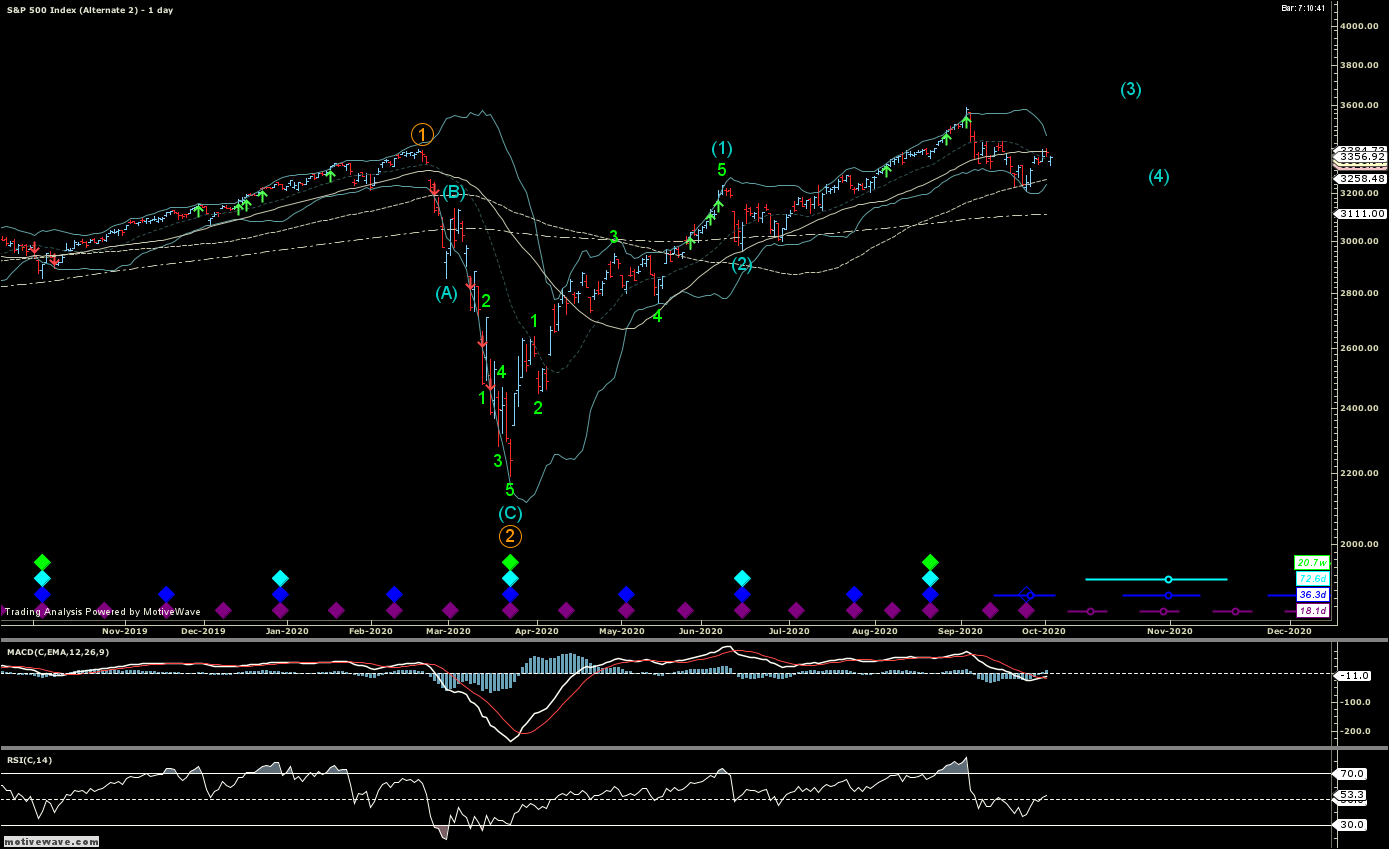

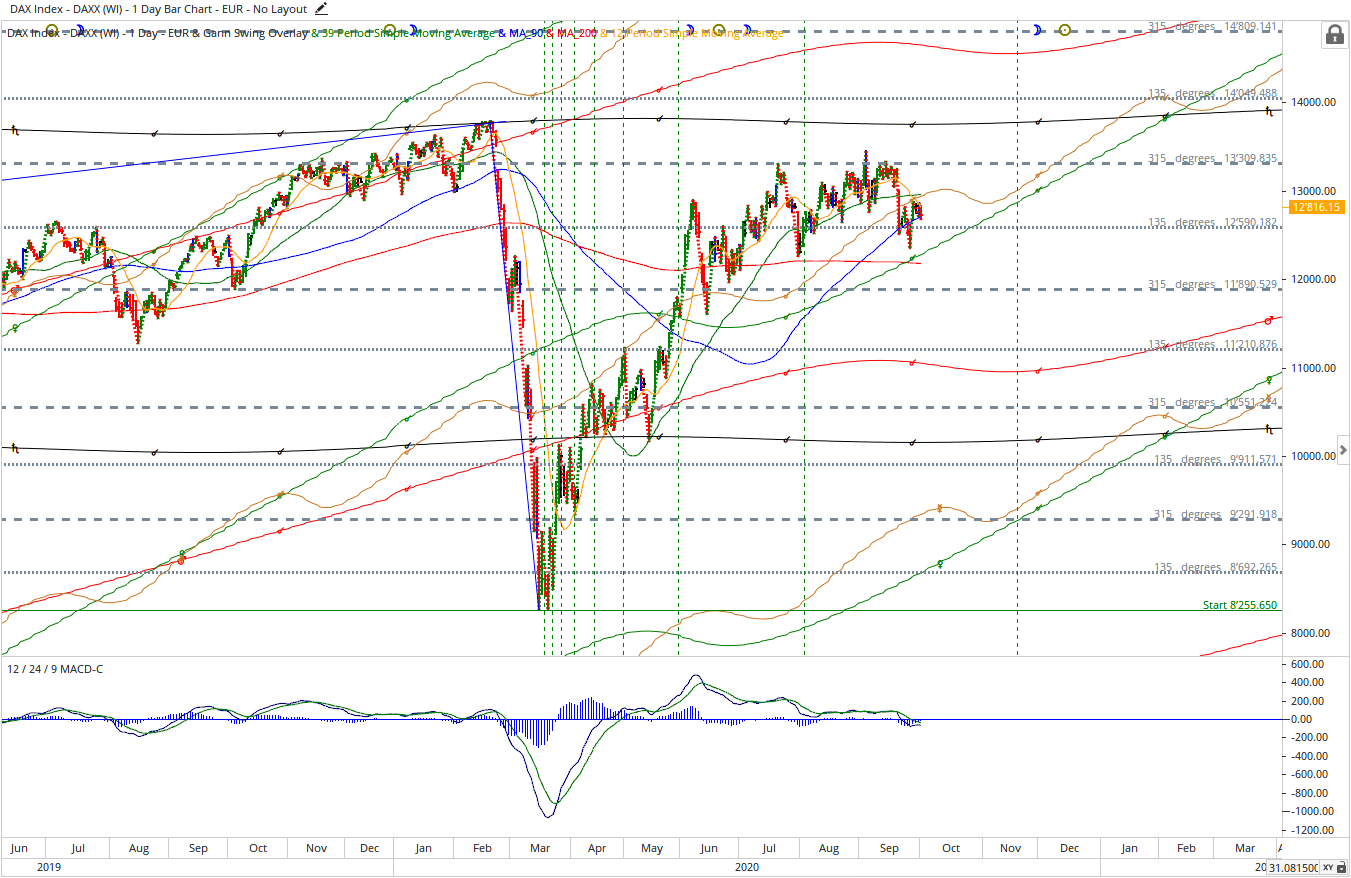

The markets lost some of their momentum in the third quarter and a consolidation was imminent. In the last third of the quarter, at the beginning of September, the markets came under pressure and in some cases undercut the last high of June. To a certain extent, there is a parallel to this compared to the year 2000, when the Internet bubble burst with the high of 1 September and market prices began to slide into a bear market.

We still think that the upward trend is intact. However, it is possible that the current phase of weakness is still spreading. On the DAX, we were on an important support line at around 12,250, which we must be able to maintain. A break could easily push it further percentage points downwards. There is a point on the time axis in mid-November where a trend-setting impulse is possible.

With the all-time high of August gold has confirmed the upward trend or dispelled the last doubts. A correction within this uptrend is underway and has lasted at least until the end of this quarter.

With regard to the breadth of the market, the situation has improved to the extent that the broader masses caught up a little during the quarter. Thus, the relatively few stocks that led the brilliant recovery lost a little ground and the lagging stocks were able to hold their own or even make gains in some cases.

Outlook

The virus and the measures taken are affecting our lives, and the course of the economy. In terms of capital markets, however, one could argue that the virus did not change too much. The virus accelerated an already existing development. Deflationary tendencies dominate the scene. For example, the US Fed is currently buying around twice as many bonds in the market as are being issued by the Treasury. That is to say, the net central bank money supply will be reduced. As long as banks do not issue enough loans or the economy does not demand enough loans, the deflationary tendencies will persist. The money supply is growing too tentatively. As a result, we continue to see low interest rates. With the banks’ excessive reserves at the central bank (Fed), it can be said that everything needed for inflation to catch fire is ready and waiting. All that is missing is someone with a match.

Capital looking for returns is parked in the stock markets – and will continue to be invested there. Here, too – similar to the situation with loans, where expansion is necessary to prevent deflation – new money or capital is always needed to maintain the level.

Because the winners of the last few years were mostly growth stocks, even those with less substance. On the one hand, this may be due to the environment of low interest rates, which has a beneficial effect on the financing of such companies. On the other hand, there is also the increased emergence of passive investment vehicles, which put stock market capitalisation in the foreground and thus have contributed to the momentum.

Long-term strategies based on profitability of the company and the substance of the balance sheets should pay off in the long term. Companies with solid balance sheets, pricing power and a healthy cash flow have good cards in their hands to weather difficult times such as the current economic weakness and a possible, deeper, recession. The art is in bringing a good mix into a portfolio. If you want to sleep peacefully, stocks with sometimes unspeakably high valuations are not necessarily recommended – sooner or later they have to provide evidence that they are worth the money. Because on the stock exchange, only the prices are traded, but the value of a company reveals itself over time – and it pays.

“The dumbest reason in the world to buy a stock is because it’s going up.” — Warren Buffett

Yours sincerely,

EDURAN AG

Thomas Dubach

Leave a Reply