EDURAN NAVIGATOR

Quarterly Market Review with an Outlook.

Zurich, 6th October 2021

“Wave break” As inflation rises, markets stall. The markets are also taking things into their own hands to a certain extent while central banks are trying to keep the yield curve under control. Whether interest rates continue to rise or not, both instances could result in an ebb in credit expansion. If interest rates increase, it could become challenging for many borrowers; if they decrease, the “margin of error” for credit-expanding banks will shrink and loans will be issued more selectively. Waves break when the height reaches 1/7th of the length. Mountains of debt grow over time before they are reduced in one way or another. Whether or not we are reaching this turning point remains to be seen.

Market Review

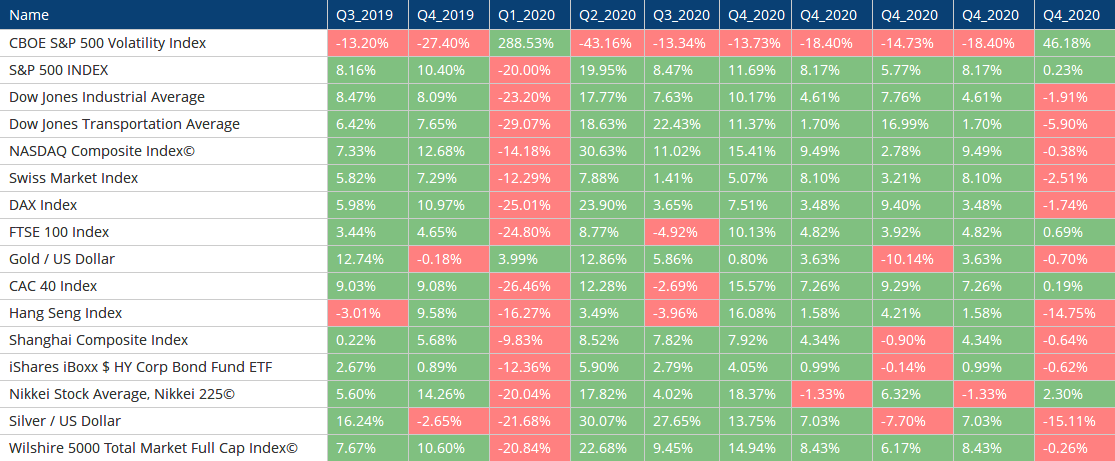

To some extent, the third quarter was a continuation of what began in the second quarter: further consolidation. This sums up the key events, based on price trends, stocks, and raw materials, as well as – if we take a look at the big picture – interest rates. Every market commentator is talking about inflation, and the idea that the increase in prices may not be temporary has become more or less established. Now that broad portions of the global economy have reopened, which has resulted in supply chain interruptions and reduced capacities due to forced closures, the increase in the price of many products, components and services should only be temporary – just until everything is back up and running and working properly.

Given the fact that the stock markets have tended to finish out the second quarter at the upper end of the range, they tended to finish out the third quarter at the lower end of the range. This was mainly due to the last third of the quarter, or the last week of September. A mixture of economic fundamentals, developments in the number of COVID cases – also in connection with vaccinations, and the bad news out of China regarding Evergrande caused many investors to take a cautious approach. Chinese markets suffered the most as a result. Once you scratch the surface of the impressive growth figures presented by China, what you find could send a chill down your spine: debt financing to a far greater degree that what we are (still) used to here in the West. More than 150% debt for some companies, whereas in the US, for example, it’s only 80%. All these uncertainties led to even greater fluctuations, as demonstrated by the increase in the volatility index.

The differences between sectors were relatively minimal: all of them left the third quarter more or less unchanged in one form or another. Manufacturing sectors, e.g. the industrial sector, continued to suffer due to gaps in the supply chain. The financial sector once again profited from the slightly steeper yield curve, which is likely to rise even more drastically.

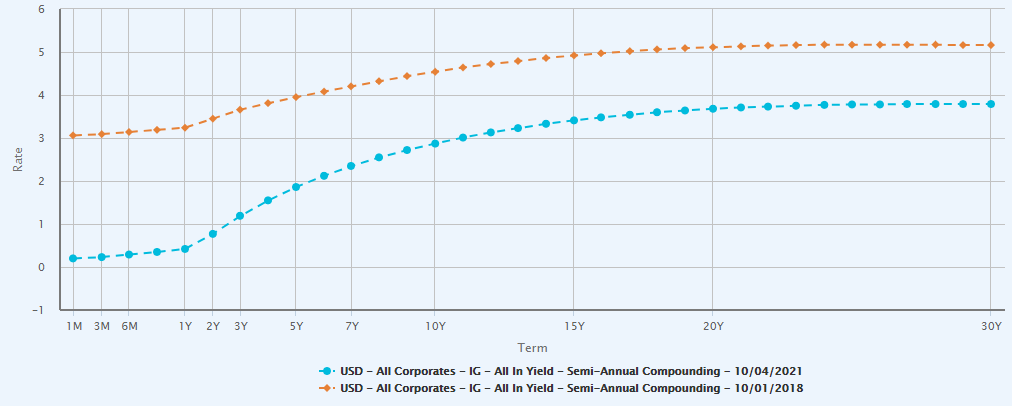

In terms of interest rates, the third quarter saw a renewed surge in yields. After the most recent peak in March of this year, yields have consolidated and are now once again taking off in the direction of pre-pandemic levels.

The steepness of the yield curve proved to be relatively unchanged in the third quarter after increasing since the “COVID correction”.

The Evergrande crisis has demonstrated that even in the era of modern monetary theory, certain physical laws still exist in the financial sector: debts either need to be refinanced (which requires sufficient liquidity) or paid back. Otherwise, companies face the threat of bankruptcy with losses for creditors. Or the debt is simply inflated away.

When it comes to currencies and raw materials, we are seeing a stronger US dollar, including compared to the Japanese yen. When we look at currencies from the large currency pools, a weak JPY (carry trade) rather suggests intact investment activities, meaning that trust does not appear to be severely damaged.

In terms of gold, you could say we are seeing the negative correlation to the development of interest rates. However, gold is also known to be an opaque market that takes on a life of its own from time to time. Gold is something you keep in a safe or in your portfolio as a sort of insurance or a sedative – at the end of the day, it has always proven its value.

In Focus

The Evergrande debacle has once again made this clear. After placing a great deal of trust in the Chinese growth story, the other side of the coin is becoming evident: as we are now seeing, extreme growth in a relatively short period of time could only be bought with relatively high debt levels. We also see this tendency here in the West; however, thanks to our structures with a more or less free market and checks and balances, we are still in a somewhat better position. And yet, we are poised to move in the same direction. It raises the question of when and how the situation will be settled. Will it be through higher interest rates, e.g. when inflation rises and it becomes more difficult to refinance? Or will interest rates once again drop back down towards zero, which will make it difficult to generate enough income to pay back the debt burden? Some say we are currently on the way to moderate inflation coupled with slow growth. Then the savers, the middle class who do not have a large number of assets, are the ones who will pay. This, on the other hand, will lead to social tension and political unrest. We continue to agree with Robert Heinlein: TANSTAAFL (“there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch”).

In terms of inflation, the current situation is reminiscent of the 1970s, even though many things are different today (at that time, the post-war generation or the Baby Boomers, were starting to enter the workforce; today they are retired, and the next large generation, the Millennials, is smaller). However, in 1973 when inflation reached 5.3% as measured by the CPI, US Federal Fund interest rates were 6.75% (at this time, the US dollar underwent a major correction compared to the price of gold). Back then, the Fed predicted that prices would increase temporarily, also due to the unemployment statistics, which were around 5% and moving towards 4%. As a result, inflation was also supposed to sink to 4% according to the models. But that was not the case. In October 1973, the oil crisis began – the supply shock of the era. Around two years later, in 1975, inflation was around 10% measured by CPI. Unemployment was 9%.

Sure, many things were different then. But with a supply shock and an academically inclined central bank that is perhaps overly reliant on models, there are certain parallels. The money supply is also rapidly expanding at the moment. Based on the M2 measure – which includes cash plus checking and savings deposits, money market securities and other term deposits – the stimulus money distributed by governments has caused this expansion has reached a new level.

At the same time, the Fed is siphoning off excess liquidity by selling securities to commercial banks. The money is not invested in the economy, but rather is essentially returned to the Fed (it is repurchased overnight at a lower interest rate).

The power struggle between inflationary and disinflationary or even deflationary forces could go into the next round. However, the situation will come to a head eventually, either in the form of currency devaluation or debt write-downs. The wave will break, the mountain of debt will crumble (or the air will leak out of the balloon).

Outlook

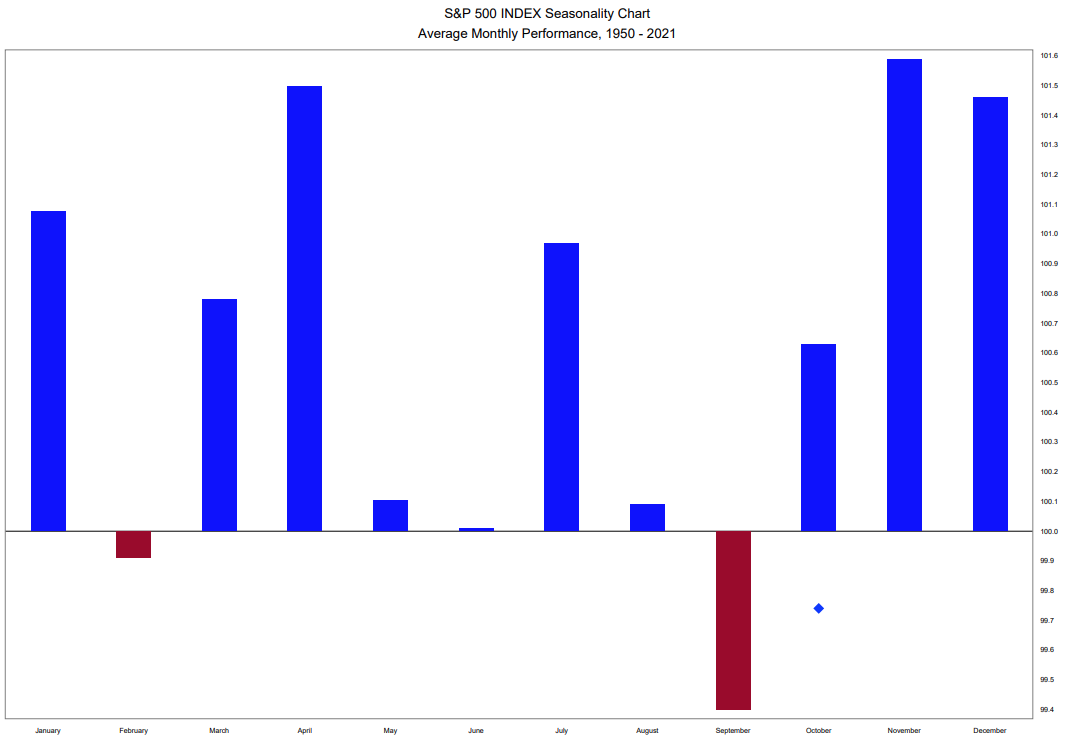

October is notorious for being a difficult month on the stock markets: the stock market crashes in 1929 and 1987 occurred in this month, as did the mini-crash in1989 at the start of the Gulf War and the Asian financial crisis of 1997. However, statistically speaking, September is actually the weakest month for the markets.

The correction that was heralded in September of this year is now the longest ongoing correction by number of days since the crash in March of 2020 due to the onset of the pandemic. Yet, if we look at loss, the correction appears to be (or is still) relatively limited. At the end of the quarter, we came close to some key support lines and, in some cases, crossed them – or at least scratched them (intraday) – however, we will see in October whether or not it is (another) poor month, or something even worse. The pending economic data will provide us with a few dashes of color so that we can paint a better picture. The crucial question remains: Are we seeing a correction or a trend reversal? The future remains uncertain, but we can imagine certain scenarios. In our view, the main drivers of the market boom remain in place: money is cheap, interest rates are low, there is an investment crisis. If there is truly an interest rate turnaround and rates increase in the direction of the levels from October 2018, this could result in a regime change. At the moment, all we can do is wait and see how the situation develops on the supply side of the economy, or even on the demand side, depending on how the pandemic evolves. Economists from Aberdeen Standard Investments estimate that the damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will amount to more than 3% of the global economic output over the long term.

With decelerated growth and increasing inflation, people are discussing whether or not we will see a period of stagflation. It appears that central banks do not have many options left. But there are already voices calling for investors to stop buying up loans at the long end of the yield curve. After all, low interest rates put wage earners, who do not benefit from the increase in value of financial assets and who rely on interest income for their retirement plans, at a disadvantage. We cannot say at the current moment whether the situation is ready for a turnaround. However, we fear that a reversal is becoming increasingly likely over time. Similar to a wave that rises up only to collapse in on itself.

“It’s better to be approximately right than precisely wrong.” Warren Buffett

EDURAN AG

Thomas Dubach

Leave a Reply